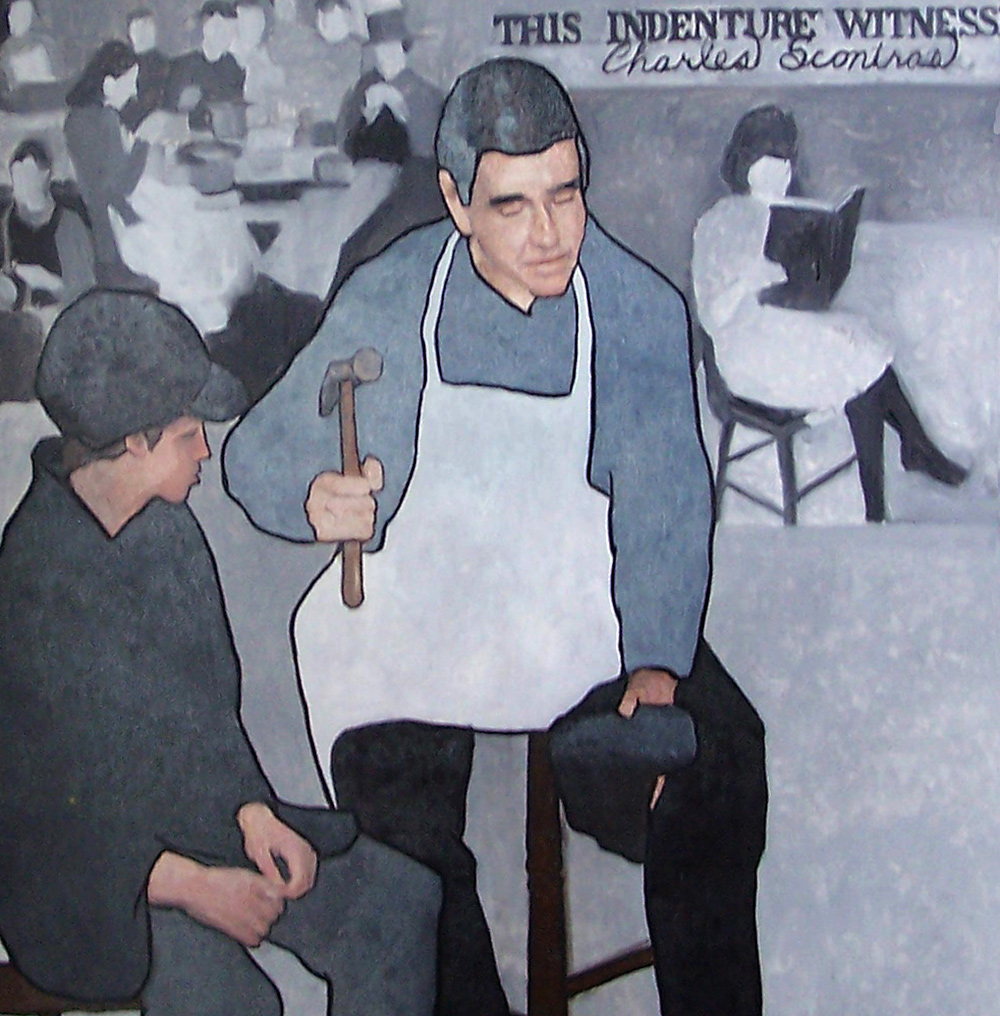

The panel’s foreground depicts a shoemaker and his apprentice. The shoemaking industry provides an example of changes in production of consumer goods over time. At first, on farms and in rural frontier conditions, families wore home-made shoes. As towns grew, artisans set up shop often in their home and contracted with apprentices. Individuals placed custom orders called "bespoke work," meaning to order in advance. In this system, the shoemaker’s personal reputation depended on the quality of his work and determined his business success.

In the early 1800s, skilled urban craftsmen, or "mechanics," began "sale work." They made shoes to sell from their shops’ shelves, from a peddler’s wagon, and later via railroad shipments in stores far from the shoemakers’ shop. To keep up with these new market demands, owners reorganized work. Craftsmen introduced efficiencies to speed production, including piece work and new technologies. Machines intensified a division of labor where a worker only made parts of a final product. The relationship between the craftsman and his work became less a matter of pride and more a matter of production goals. Quantity and not quality became critical in turning a profit.

As technology changed, the "mystery" or trade secrets imparted from master to apprentice became lost or irrelevant. Until the Civil War, most workers continued to be employed in small shops, but the structure of work steadily changed. With the uncertainty of distant markets and the need for flexible production, masters no longer wanted to commit to employing, feeding, and housing apprentices for years at a time. They preferred to hire workers as orders demanded. While shop workers at all levels once held shared interests, conflicts emerged between the master and his journeymen and apprentices over hourly pay, time, and working conditions. Remnants of the apprentice system exist today in certain trade unions, such as plumbing and electrical, in which the apprentice and journeymen titles are still used.